Recent attention has been given to rare or orphan diseases—more specifically, to the costs associated with the drugs that treat them. To better understand the reasons behind the increased attention and scrutiny given to orphan drugs, it’s first important to understand the history behind them. What exactly are orphan drugs and how did they come about? Why are we seeing more of them? And why are they so costly? In this journey of orphan drugs, we will learn the answers to these questions.

Prevalence & Severity of Orphan Diseases

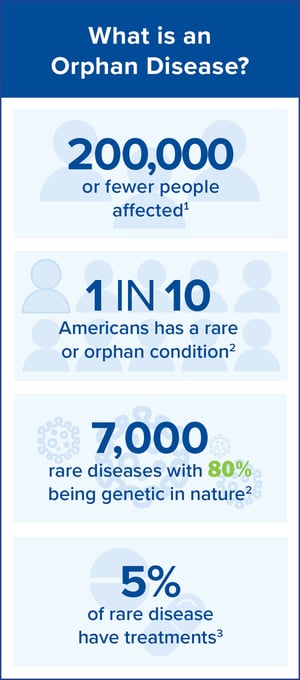

An orphan disease is defined by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a condition that affects fewer than 200,000 people nationwide.[1] In fact, it is estimated that nearly 30 million Americans—or 1 in 10 people—have one of the approximately 7,000 identified rare diseases.[2] Genetic disorders make up about 80% of these rare conditions.[2] Surprisingly, only 5% of rare diseases have treatment options available.[3] This is due to the cost considerations associated with developing targeted drugs to treat a small population.

An orphan disease is defined by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a condition that affects fewer than 200,000 people nationwide.[1] In fact, it is estimated that nearly 30 million Americans—or 1 in 10 people—have one of the approximately 7,000 identified rare diseases.[2] Genetic disorders make up about 80% of these rare conditions.[2] Surprisingly, only 5% of rare diseases have treatment options available.[3] This is due to the cost considerations associated with developing targeted drugs to treat a small population.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), cystic fibrosis (CF), which effects 30,000 Americans, is the most common and fatal rare genetic disease we face in the U.S.[4] The financial burden of the disease is staggering, with medications being the single largest expenditure. The average medication spend for this disease was upwards of $50,000 per person per year and with new, targeted treatments, those expenses are even more. As an example, Trikafta® costs $300,000 per patient per year and that doesn’t even include medically associated costs, such as hospitalizations, doctor’s visits and durable medical equipment used as part of the daily CF therapy. Nor does it consider the patient’s lost time from work or school. Other examples of orphan diseases include certain types of cancer, hereditary angioedema, hemophilia A and B, Lou Gehrig’s disease, Rett Syndrome, and Tourette’s syndrome, just to name a few.

History Behind Orphan Drugs

While FDA regulations in the 1960s promoted the increased development of new drugs, it dramatically slowed the momentum for the development of drugs to treat rare conditions. Pharmaceutical companies were financially motivated to develop treatments for common diseases that treated large populations vs. rare conditions that treated small populations because of less return on investment.

The term “orphan” was first used in medical context in 1968 in a Journal of Pediatrics article entitled, “Therapeutic Orphans.” In this article, Dr. Harry Shirkey was quoted as saying that there was inequality for drugs to treat children since fewer drug developers found it cost effective to study the safety and efficacy of drugs in children. As a result, infants and children became “therapeutic or pharmaceutical orphans.”[5]

Equivalent to a modern-day hashtag trend, others quickly followed suit with his terminology, applying “orphan” to other types of diseases they felt were abandoned. Even advocacy groups became more vocal for change. They realized the need for government intervention to properly motivate drug manufacturers to research and develop more orphan drugs. In 1982, one advocacy group formed an informal coalition asking for governmental support. This coalition would later be known as the National Organization for Rare Diseases (NORD), which led to the Orphan Drug Act of 1983 signed by President Ronald Reagan.

Equivalent to a modern-day hashtag trend, others quickly followed suit with his terminology, applying “orphan” to other types of diseases they felt were abandoned. Even advocacy groups became more vocal for change. They realized the need for government intervention to properly motivate drug manufacturers to research and develop more orphan drugs. In 1982, one advocacy group formed an informal coalition asking for governmental support. This coalition would later be known as the National Organization for Rare Diseases (NORD), which led to the Orphan Drug Act of 1983 signed by President Ronald Reagan.

Tax Credits, Grants and Market Exclusivity, Oh My!

The Orphan Drug Act (ODA) incentivized manufacturers to develop drugs to treat rare or orphan conditions by providing tax credits up to 50%, waived application fees, a seven-year marketing exclusivity period, research grants, and a government-run enterprise to continue momentum on research and development.

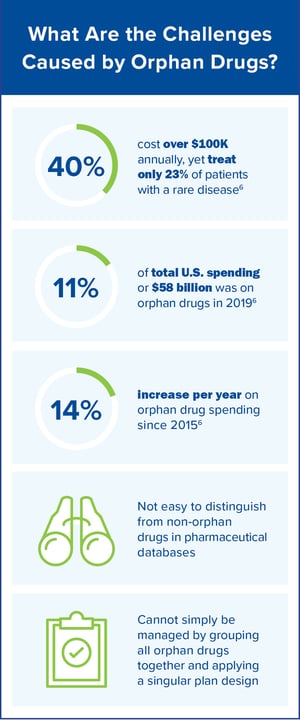

It is evident that there continues to be a clear need for the development of drugs that treat rare conditions. It is also evident that some manufacturers have faced challenges in seeing their return on investment to develop a complex drug that only treats a small population. The ODA was created to reward pharmaceutical manufacturers for developing drugs for rare diseases. From the employer group and health plan standpoint, there are challenges to offering a viable prescription drug benefit for orphan drugs. How do we ensure these medications are medically appropriate? How do we appropriately manage them?

As the orphan drug market continues to increase in both the number of available products and costs, solutions are needed to help members achieve their best whole health while managing spend.

[1] Food and Drug Administration. Developing Products for Rare Disease & Conditions. https://www.fda.gov/industry/developing-products-rare-diseases-conditions.

[2] Global Genes. Rare Facts. https://globalgenes.org/rare-facts/.

[3] America’s Biopharmaceutical Companies. Rare Disease by the Numbers. https://innovation.org/en/about-us/commitment/research-discovery/rare-disease-numbers.

[4] National Institutes of Health. About Cystic Fibrosis. https://www.genome.gov/Genetic-Disorders/Cystic-Fibrosis#:~:text=Cystic%20fibrosis%20(CF)%20is%20the,United%20States%20have%20the%20disease.

[5] Sasinowski, Frank J., Hull, Andrew J (2015). A Brief History of the Name ‘Orphan Drugs.’ MedCity News. February 22, 2015. https://medcitynews.com/2015/02/brief-history-name-orphan-drugs/?rf=1.

[5] IQVIA. Orphan Drugs in the United States: Rare Disease Innovation and Cost Trends Through 2019. December 2019.